Is Indonesia's top AI optimism globally a grounded enthusiasm or blindfolded ignorance?

Indonesia ranks as the world's second most AI-optimistic nation despite limited contributions to global AI model development and research. This article examines this paradox and its implications.

By: Mansur M. Arief, PhD

Executive Director, Center for AI Safety, Stanford University

Lecturer, Sekolah Interdisiplin Management Teknologi (SIMT), Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember (ITS) Surabaya

Adjunct Professor, Universitas Logistik dan Bisnis Internasional (ULBI)

Indonesia stands at a critical crossroads in the global artificial intelligence landscape—ranking as the world's second most AI-optimistic nation while contributing at a nascent stage to global AI research and development. This paradox, revealed in the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI)'s AI Index 2025, raises a pivotal question: Is Indonesia's remarkable enthusiasm for AI technologies grounded in genuine understanding, or does it reflect a dangerous knowledge gap that could undermine the nation's technological future?

The Optimism-Expertise Disconnect

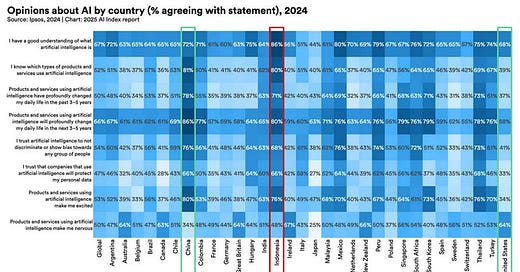

The HAI survey exposes striking contrasts between perception and reality. An overwhelming 86% of Indonesian respondents claim substantial understanding of AI fundamentals, with 80% reporting familiarity with AI-enabled products and services. Only 48% express concerns about AI technologies.

Compare this to the United States—the 2025 leader in global AI models and research output —where only 68% of respondents express confidence in their AI understanding, and 64% report apprehension about AI implications. This inverse relationship between AI production capability and public confidence presents a troubling paradox. Why are nations with the greatest AI expertise exhibiting greater caution, while Indonesia—with comparatively limited AI research infrastructure—demonstrates such unbridled optimism?

China presents a particularly nuanced case—ranking second globally in AI research output while maintaining high public optimism (72% confidence in AI understanding) and notably low concern levels (34%). This three-nation comparison raises critical questions: What constitutes an optimal balance between enthusiasm and caution? How can Indonesia develop both technical expertise and appropriate risk awareness simultaneously? And what lessons can be drawn from both Chinese and American approaches without simply replicating either model?

Three Critical Imperatives for Indonesia's AI Future

Indonesia's exceptional AI optimism has clear demographic foundations. As the world's fourth most populous nation with 275 million citizens and a substantial youth demographic, Indonesia naturally embraces technological innovation. The country ranks as the world's fourth-largest digital population and third-largest AI service visitor. Expanding internet penetration and electricity access further accelerate this digital enthusiasm.

However, enthusiasm without expertise creates vulnerability. While Indonesia eagerly adopts AI technologies, the nation's capacity to shape, evaluate, and de-risk these systems remains underdeveloped. This imbalance risks relegating Indonesia to perpetual consumer status rather than a meaningful contributor to the AI ecosystem. Converting Indonesia's AI enthusiasm into tangible societal benefits requires a multifaceted approach that transcends mere optimism. Three critical domains warrant immediate attention:

Educational Transformation

Indonesia must develop a comprehensive AI education framework that emphasizes critical thinking, creativity, and human-centeredness, over rote learning paradigms. The older educational system, which often prioritizes memorization over analytical skills, must be reformed to nurture a generation capable of harnessing AI's potential and escaping its replacement.

As Rizki Oktavian of MindSTEM.id, a research scholar in Purdue Nuclear engineering and an adjunct professor at ULBI, states: "Education should prioritize developing critical thinking over traditional methods. Assignments should be designed with the assumption that students have access to AI, and should focus on high-level, thought-provoking problems. Educators also need to understand where and how AI should be used, as well as where it should not." His organization invites Indonesia’s diaspora to share practical tips and knowledge in the STEM field to the larger Indonesian audiences through free webinars and workshops. Such an initiative plays a crucial role in the broader context of strengthening Indonesia’s core critical thinkers through re-envisioned educational activities.

This requires redesigning assessment methods to evaluate conceptual understanding rather than information recall, and developing faculty expertise in AI-augmented education. The Vice President of Indonesia's recent call for an AI curriculum in schools represents a positive step, but must be implemented with careful attention to developing higher-order thinking skills and national-scale readiness.

Collaborative Governance

Indonesia requires a cohesive, cross-sector approach to AI governance. The commendable efforts of Satu Data Indonesia, a Bappenas-led initiative in centralizing data governance, represent a positive step, but require complementary initiatives from private enterprises, academic institutions, and non-profit organizations. "We work with UNESCO and various stakeholders, including leading researchers in the field, to develop a framework for AI governance that is inclusive and transparent," says Dini Maghfirra, the executive director for Satu Data Indonesia. As nations worldwide grapple with the ethical implications of AI, Indonesia must proactively engage in discussions surrounding data privacy, algorithmic bias, and accountability.

Effective regulation must balance protection of public interests with innovation enablement—a delicate balance requiring diverse stakeholder input. It requires both technical understanding and cultural contextualization—capabilities that must be cultivated simultaneously. Without this balanced approach, Indonesia risks developing governance frameworks that either stifle innovation or fail to adequately protect citizens from potential AI harms. The nation's unique cultural and linguistic diversity demands governance models specifically tailored to Indonesian contexts rather than simply importing regulatory approaches from Western or other Asian nations.

Contextual AI Development

Indonesia must prioritize AI safety awareness while developing contextually appropriate applications. Foreign-developed foundation models trained on internet-scale data cannot adequately address Indonesia's unique challenges without significant adaptation. With Bahasa Indonesia representing merely 1% of internet content, off-the-shelf foundation models trained using the Internet data likely fail to capture cultural nuances and may perpetuate harmful biases.

This necessitates investment in Indonesian-language datasets and evaluation frameworks to ensure AI systems serve local needs appropriately. We have great AI, informatics, and computer science researchers at many Indonesian institutions but they need additional resources and capacity to scale up what they can do given the even faster AI industry developments. Moreover, Indonesia must initiate a context-specialized AI evaluation framework for foundation models deployed in Indonesia to address uniquely Indonesian challenges in various critical sectors.

The Hidden Dangers of Algorithmic Bias

Our research at Stanford Center for AI Safety reveals a concerning pattern in how emerging AI tools interact with Indonesian language and context. When examining code completion systems, we discovered these tools inadvertently encode societal biases into their automated suggestions. In a demonstration analyzing teacher salary prediction functions, the AI consistently generated code that applied a lower salary multiplier (0.9) to "perempuan" (women) while assigning a higher multiplier (1.1) to "laki-laki" (men) teachers. This was not programmed intentionally, but emergent naturally perhaps due to the biases in the AI training data.

A similar study examining whether off-the-shelf large language models (LLMs) can serve as military strategic agents revealed concerning tendencies toward conflict escalation. While researchers couldn't pinpoint the exact source of this bias, the nature of internet content—often confrontational rather than collaborative—offers some explanation. Training LLMs on internet-scale data inherently preserves existing conflict escalation patterns, which can amplify when systems are deployed without proper oversight.

These findings highlight a broader challenge: as AI development accelerates, unsupervised code generation through readily available tools becomes increasingly common, yet the resulting algorithms may silently perpetuate or amplify existing inequities. Without culturally-aware evaluation frameworks, these biases remain invisible until implemented at scale, potentially affecting millions of Indonesians. This example underscores why technical understanding must accompany AI enthusiasm—Indonesia must build capacity to identify and address these biases within its unique linguistic and cultural context.

In the United States, machine biases have been documented. A landmark example is the ProPublica investigation "Machine Bias" that revealed how predictive algorithms used in criminal sentencing displayed significant racial disparities, falsely flagging Black defendants as future criminals at nearly twice the rate as white defendants. Finding such vulnerabilities is an active area of research both from academia and industries across various application domains.

As Bayu Aryo Yudanta, a PhD student in the School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences at the University of Pittsburgh noted, "Bias frequently emerges when training data and deployment contexts misalign—a common scenario in healthcare applications." Indonesia's diverse linguistic and cultural landscape requires AI systems specifically adapted to local contexts, which presents both challenge and opportunity for developing culturally responsive AI solutions. But it needs everyone's involvement—from government agencies to grassroots communities.

“An interesting proposal from the healthcare domain where data privacy is crucial and biases and context-ignorance can lead to fatality at large scale is federated learning. The idea is to decentralize AI model training into each institution (i.e. hospital) where private patient data can be stored securely and only share model weights to other partner institutions where the model can be further trained. The process is carefully orchestrated to ensure localized contexts are maintained but global and useful patterns are reconciled. The data also remains in safe storage. The risk is controlled and minimized,” Bayu explained.

From Optimism to Actionable Path Forward

These advances overshadow huge potential for our path forward. Indonesia must chart a course that capitalizes on its remarkable AI enthusiasm while simultaneously developing technical capabilities, risk awareness, and regulatory frameworks. Rather than simply emulating American caution or Chinese confidence, Indonesia has the opportunity to pioneer a uniquely balanced approach that reflects its cultural values and developmental priorities by capitalizing on this latent optimism potential. The ultimate measure of Indonesia's AI success will not be found in optimism metrics but in tangible applications that enhance citizen welfare, economic productivity, and institutional effectiveness while mitigating potential harms. To make it happen, we need to balance optimism with AI talents and AI safety capacity building.

Indonesia stands at an inflection point: will its AI future be defined by informed leadership or by passive consumption? The answer depends on whether today's enthusiasm can be channeled into tomorrow's expertise.